‘Self-publishing is an act of defiance against the system’ OR ‘beeboobeeboo I didn’t get a publisher for The Witch of Benbar’s Cross (but also: fuck yeah)’

You know that saying ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same’?

Of course you do.

Well, after bitching for a year that I Do NoT wAnT tO SeLf-PuBlisH EvEr AgAiN, here I am about to self-publish again.

Contrary to my incredibly high hopes and near certainty that I would land a traditional publisher for The Witch of Benbar’s Cross, I have in fact heard nothing but crickets from international agents and publishers, and the gentle sloshing of the slush pile from a local publisher. A sloshing that sounds terribly, offensively loud in this very small local fishpond.

‘But how is this possible, Tanya?’ I hear the voices in my head you cry. ‘You are so brilliant and amazing and your stories a boon to all who read your work! How are the powers that be not recognising this supreme gift you have to offer the world?!’

Thank you, thank you, I know, I know. It is a karmic burden it appears I must carry.

Sigh.

In truth, after pitching the first 10 agents and publishers, I quickly realised I was unlikely, yet again, to get a foot in with trad publishers.

My work, I think, falls into a difficult middle: too different from the norm to find a comfortable publishing home, but not different enough to find a comfortable publishing home.

And, of course, not South African enough for South African publishers. If our general fiction publishers are anything to go by, writing a story that isn’t somehow South African is a pleasure reserved for only one lucky South African English author every mystical five or so years.

Anyway.

So I pitched another 10 agents and publishers just for shits and giggles and then decided to call it quits.*

In the past this would’ve really bummed me out, but this time it didn’t.

This time, I decided to prioritise my mental health (pitching is a kind of hell) and shift my perspective from a ‘poor me’ to a ‘fuck yeah me’ and honour my art over my expectations.

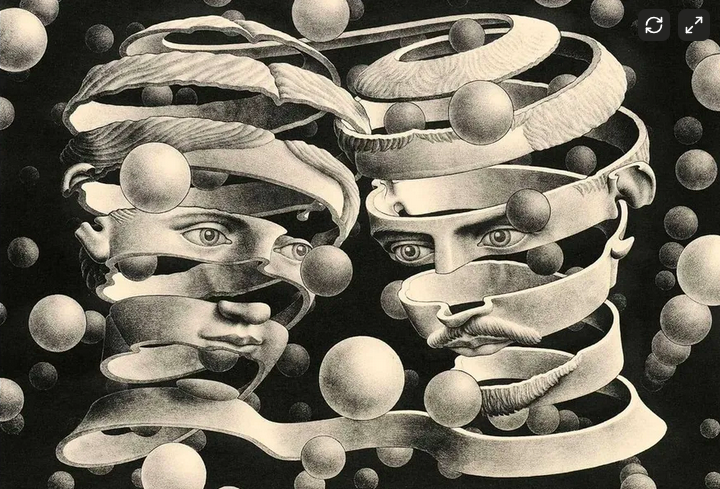

I decided that I will dive head first into the acceptance of what each of my books is: an art piece, totally self-created**, totally mine, from cover to cover. I write the words, I typeset the words, I create the cover, I get it printed, I send it out to readers and bookstores, I have total ownership of it.

It is mine, totally and completely, and when it is done and a reader connects with it, they’re connecting with me, totally and completely. Typos and all. (Here’s to you King Louise! IYKYK.)

That’s kinda cool and that’s what I’m going with. Besides. I simply do not have the patience or anxiety reserves to keep knocking on doors. I have other books to write and get out and researching and chasing agents gobbles not an insignificant amount of time and energy.

But that’s not to say I’m totally and completely thrilled about it (yet).

I’m again bummed about missing out on the easy market relevancy that trad publishing comes with.

People need (want?) to be told what’s worthwhile

It’s something all self-published books miss out on: the signposting of a corporate logo to the market.

When a publisher plucks a book and its author from obscurity, it tells the market—readers, festival organisers, book clubs, awards, book store managers, media types, reviewers—that this book and its author have been vetted and vouched for and found worthy of your eyeballs, space, time, and spend.

Next to book production and distribution, market relevancy is what makes trad publishing worth it for authors, although most don’t realise it.

Or appreciate it for that matter.

I’ve enjoyed watching some new authors get every platform available and still refer to themselves as ‘outsiders’ and ‘underdogs’.

Anyway.

Trad publishing and how it marks an author as relevant is what helps your book creep out of that first readership bubble that’s comprised of friends, family, and close community.

I always tell my self-publishing clients that a reader’s journey with your book starts with the bookshelf they’re standing in front of in the book store and then the book’s cover. But in wider terms, it starts with the publisher’s logo.

Without it, you’re always just standing on your own soapbox shouting for someone to pay attention. A really big ask given the hundreds of books readers are bombarded with every week.

So having to get on my little soapbox is crap and not something I’m super looking forward to. But, still, the way publishing is going, I’m feeling less sour about it every time.

Self-publishing: Rage against the machine

The publishing industry has always been a numbers game. And writers, typically not of the hustling mentality, have been ignored or snapped up and spat out for as long as the business model has been around.

I like to remember this when I’m feeling less than thrilled about self-publishing and I like to remember all those extremely awesome writers who paid for their own books to be published or simply set up their own publishing businesses to get their work out.

Benjamin Franklin published his own work, as did William Blake, Beatrix Potter, Virginia Woolf (‘Publishing one’s own book is very nervous work.’), Margaret Atwood, Mark Twain (You might have heard of Huckleberry Finn? To be fair, he was already famous at this point, he was just sick and tired of publishers.), Edgar Allan Poe, EL James, Sarah Maas, and Colleen Hoover. And, of course, Jane Austin who published Sense and Sensibility on a hybrid basis: she was responsible for the production and advertising costs and received a percentage of the sales.

The reason I mention this is not to align myself with these esteemed (and less esteemed authors, sorry ‘James’), but rather to remind myself—and other nervous self-publishers—that very often, most often, self-publishing is an act of defiance against a system that is becoming increasingly beholden to churn as belts tighten and accountants call the shots on which authors get the go and which the no-go.

And I get it. Publishing is a gambler’s game, no matter how snooty it likes to come across.

With fewer readers and less money, publishers probably feel that it’s better to place their chips on the most likely winners most likely to appeal to as broad a market as possible.

There’s no need for me to go into what a bad thing this is for literature when you can read a great article about it here > The Big Five Publishers Have Killed Literary Fiction. (Although, I’d hazard a guess that the same problem is affecting indie presses to some degree, something neatly exemplified by the fact that Woolf’s own Hogarth Press turned down James Joyce’s Ullyses because it was too long.)

If it’s bad for literature in general, it’s bad for authors in particular.

It means many talented authors that don’t contribute to the churn don’t get a second look. It means that current authors get dropped the minute their books don’t hit projected sales targets. It means that new authors who still labour under the ‘shame’ of self-publishing will hurt themselves for years trying to get signed and eventually give up.

But that’s not me, friends. I’m far too pig-headed about my stories.

Coming to a book shop near(ish) you in 2026

The Witch of Benbar’s Cross will be out early next year. She’s going into production next week, and that means editing and book cover, typesetting and proofing, getting barcodes, setting up marketing material, booking a launch…

You know, as I type this out, I’m feeling less and less poesagtig about it. This part is fun. It’s my art. It’s my creation. And that’s never a bad thing. Never.

Now if only I could start feeling that way about marketing and that soap box…

Over and out light buddies,

t

* After The Fulcrum, I don’t believe in pitching a million agents.

** This time, I’m getting a line editor and proofreader on board. So not 100% solo effort in that regard.